By: Kari Nixon

June 26 2024

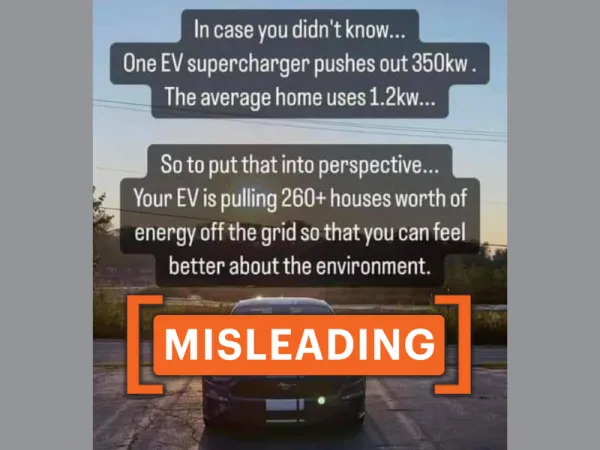

An infographic shared on Facebook claims that electric vehicle superchargers use more energy than an entire household.

An infographic shared on Facebook claims that electric vehicle superchargers use more energy than an entire household.

Electric vehicle supercharging does not use more energy than a household. This infographic confuses total power used versus speed of power given.

The claim

Social media users are circulating an infographic claiming that electric vehicles (EVs) use more energy than the average household. The Facebook post, archived here, has garnered over 20,000 views, and states that "One EV supercharger pushes out 350 kW. The average home uses 1.2 kW. So to put that into perspective…your EV is pulling 260+ houses [sic] worth of energy off the grid so that you can feel better about the environment.”

The purpose of superchargers is to more rapidly charge electric vehicles.

However, the numbers in this infographic are inaccurate.

In fact

Over the course of an average year driving, an EV uses approximately 4,310.65 kW, whereas the average household usage is 10,500 kW per year.

In addition to this discrepancy, the infographic leaves out several pieces of crucial information necessary for comparing EV energy usage with household energy usage.

The first is that it confuses maximum voltage capacity – the output that could be used to charge an EV – with the voltage that might actually be used.

We contacted Leander Spyridon Pantelatos, a PhD student studying battery usage and sustainability at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, who provided insight into how such charging methodologies work.

"Many of the current EVs also reduce the charging power at a higher state of charge (SOC) to save the battery a little. So, the 350kW is more a theoretical maximum which is not really utilized in practice,” according to Pantelatos. He directed us to an infographic from the academic journal Energies, which demonstrates that even 300kW is almost never achieved.

A graph comparing the different energy uses of different charging types showing that none exceeds 300kW.

(Source: Wu, Z., Bhat, P. K., & Chen, B. (2023). Optimal configuration of extreme fast charging stations integrated with energy storage system and photovoltaic panels in distribution networks. Energies, 16(5), 2385.)

Secondly, the infographic confuses the total amount of energy used with the time spent using that energy.

Professor Casper Boks of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology explained that “the 350kW in the [viral image] says something about the max power output of a supercharger, but nothing about the power use. The 1.2 kW figure says nothing about power use over time either. To compare sustainability aspects one would need to compare power use over time (choose a proper functional unit like electricity consumed in one year), not max power output at any given moment.”

He used a helpful metaphor to explain the problem with the infographic’s reasoning, stating, “It’s like saying, ‘Usain Bolt can run 4 times as fast as me, so he needs four times as much energy as me and must eat four times as much as me in a whole year,’ which is not true, of course.”

An article in UC Berkley Alumni magazine writes that “Supercharged vehicles haven’t used more energy to charge–they’ve just used it faster.” The supercharger’s main offering to consumers is that it can charge faster – the actual amount of energy used to charge the same car battery would not differ significantly.

The magazine goes on to say that this added energy usage at one time could put pressure on power grids, but the solution is as simple as spreading out these charging stations so that drivers don’t put pressure on the grid at the same time.

The verdict

This infographic misrepresents the speed at which charging can take place for the amount of energy used at one time. Therefore, we have marked this claim as misleading.