By: Devika Kandelwal

August 18 2020

Many factors drove mass incarceration, including trends that predated the 1994 law, but the law may have led to more incarcerations.

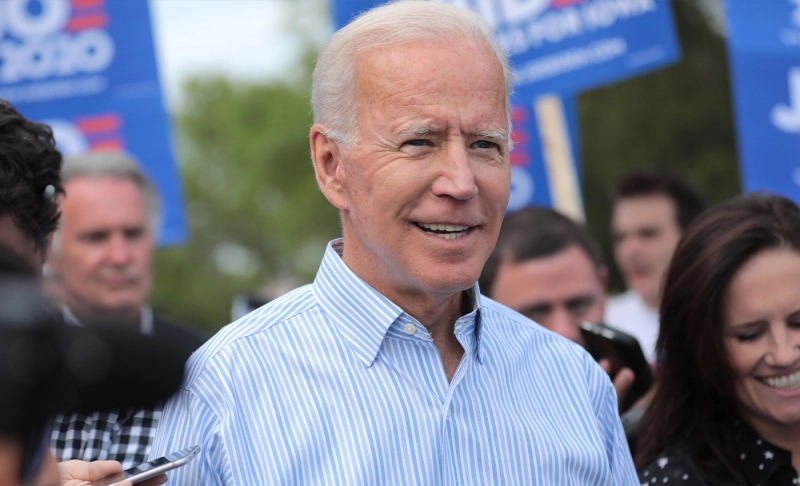

Many factors drove mass incarceration, including trends that predated the 1994 law, but the law may have led to more incarcerations. The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, now known as the 1994 crime law, passed when Biden oversaw the Senate Judiciary Committee at the time and other Democrats. The law was passed by Congress and signed by President Bill Clinton. The crime law meant to increase incarceration in an attempt to crack down on crime, but based on statistics and reports, the law did not lead to a massive rise in the prison population. The law imposed stricter prison sentences at the federal level and encouraged states to do the same. It provided funds to states to build more prisons, aimed to fund 100,000 more cops and backed grant programs that helped police officers to carry out more drug-related arrests. At the same time, the law included the Violence Against Women Act, which provided more resources to crack down on domestic violence and rape. The law encouraged states to back drug courts, which attempt to divert drug offenders from prison into treatment, and also helped fund some addiction treatment. Biden's stance on the law has varied over the course. In a 2016 interview with CNBC, Biden said that there were parts of the law he'd change, but argued that by and large what it restored American cities. Later in 2020, he apologized for portions of his anti-crime legislation. Although he has mostly tried to play down his involvement, saying in April 2020, that he got stuck with the bills because he was chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee. He also said 92 out of every 100 prisoners end up behind bars are in state prison, not a federal prison. The crime bill did not generate mass incarceration. The bill earmarked $8.7 billion over six years for states to build more prisons. About half of the money was available to states that enacted truth-in-sentencing, or TIS, laws that cut back on paroles and required people convicted of violent crimes to serve at least 85% of their sentences. A 1998 congressional study found that out of 27 states that got grants, 11 said the federal money granted by the 1994 bill played only a partial role in changing state law, and just four said it was a key factor. A 2002 Urban Institute study found that from 1995 to 1999, nine states adopted such laws for the first time, while 21 others changed existing laws to qualify for the funds. By 1999, a total of 42 states had such laws in place. At the same time, many states passed their own tougher sentencing laws, and the 1994 bill only exacerbated the trend. A 2016 analysis by the Brennan Center concluded that the 1994 bill contributed to the subsequent decline in crime and the doubling of the rate of imprisonment from 1994 to 2009. However, a crackdown on crime was on the rise at the state level before the 1994 bill came into effect, and the bill only led to a slight increase in the incarceration of people.