By: Francesca Scott , Nabeela Khan

July 10 2023

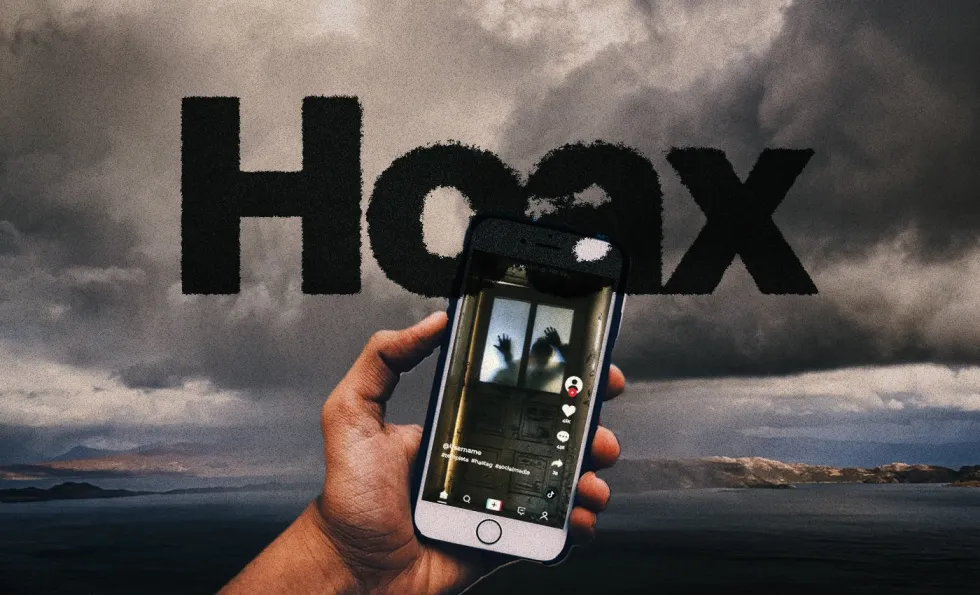

April 24, 2021, saw the birth of a disturbing internet hoax. A TikTok rumor took hold, claiming that a group of men had declared the date "national rape day." As the posts spread through social media channels, young people vulnerable to misinformation were exposed to millions of videos urging them to stay inside, carry weapons, and be prepared to defend themselves from rape. Children and teenagers are less able to assess the veracity of misinformation due to age, a lack of critical thinking skills, and media literacy – not to mention a tidal wave of content pushed by algorithms that "recommend videos that are more extreme and far-fetched than what the viewer started with." And so the same rumors appeared in 2022 and again in 2023, despite the original claim being debunked by fact-checkers. This year, a girl in the U.K. was so convinced of the threat that she reportedly brought knives to school.

This type of claim has now come to be known as the phenomenon that is zombie hoaxes: misinformation narratives that, despite being debunked, resurface year after year. Other narratives falling under the zombie hoax label include claims that black bras cause cancer (they do not), advice not to drink cold drinks after eating mangoes, that COVID-19 is a bioweapon (it is not), and countless WhatsApp hoaxes promising gifts and cash.

Much of this type of misinformation shares a horror quality - whether it be fentanyl in Halloween treats or things that go bump in the night. These familiar stories hark back to folklore and legends that have been passed down orally over generations. The online versions spread much faster and, now and again, cause real-world harm.

Perry Carpenter, cybersecurity expert, and co-creator and host of the podcast Digital Folklore, told Logically Facts, "People believe and propagate these legends because they embody our fears. Something like the 'rape day' panics acknowledge and give voice to the fact that sexual assault is a real and present danger. The possibility of being assaulted, or having a child or friend who is victimized, is an all too real possibility." When hoaxes like "rape day" appear, we are given a tidy scenario into which we can focus these fears into one convenient package.

Regarding spread, University of Southern California researchers found that the most significant influence in the reach of fake news is the structure of social media platforms, which rewards users for habitually sharing information. One of the authors from this study said, "The habits of social media users are a bigger driver of misinformation spread than individual attributes. We know from prior research that some people don't process information critically, and others form opinions based on political biases, which also affects their ability to recognize false stories online."

Dr. Cait McMahon, former managing director of Dart Center Asia Pacific – a regional hub of the Dart Center, which focuses on trauma issues in journalism – explains, "The world is shifting rapidly with computer technology and social media. To some degree, I don't think we have caught up with these tools, so my answer comes from an educated guess rather than any research base. I believe there are several factors at play here, which includes some psychology but also social and political factors."

"If we keep hearing misinformation over and over, it becomes familiar, and we tend to then believe it, and it hooks into our internal biases," she adds.

Repeating a false claim could make it more familiar, and research shows that the continued influence of misinformation is not an isolated problem, as "people continue to be influenced by misinformation even after learning that it is false across a variety of domains."

We asked Dr. McMahon how and why people continue to believe misinformation, and she responded that "in 1977, a study identified a concept called the 'illusory truth effect.' This theory identified that the more something untrue is stated repeatedly, people will believe it more readily than new truthful information not repeated frequently."

She added, "Our brains are also geared up for two very connected processes – memory and information processing. If we have something repeated many times (even an untruth), it becomes more embedded in our memory. If we recall things easily from our memory, we tend to regard them as true because it has become common to us. We call this the 'availability heuristic.' This links into a concept called 'confirmation bias,' which is that when a statement (even untruth) aligns with our already existing beliefs, we tend to accept it without challenging its accuracy. This, in turn, reinforces the illusion that the untruthful statement is true."

Some many other beliefs and claims have been debunked by science but continue to be revived many times as they align with a person's beliefs or fit into their own confirmation bias. People continue to believe that organic food is free of pesticides and more nutritious, natural sugars such as jaggery and honey are better, sharks can detect a single drop of blood in the ocean, and dairy products are fattening.

The Momo challenge spread via WhatsApp in 2019, with messages arriving from an account depicting a distorted face with cavernous eyes. The messages claimed to dare receivers into committing harmful acts and even suicide. A mix of malicious hoax and moral panic, Momo "attracted hundreds of thousands of shares on Facebook in a 24-hour period, dominating the list of U.K. news stories ranked by number of interactions on the social network." The media picked up on the hoax, inadvertently spreading it across platforms and publishing houses with explainers, warnings, and celebrities releasing concerned statements, all helping to drive the spread. But no evidence was found to connect Momo to any suicides. In hindsight, the hoax took on the characteristic of online folklore, becoming more of a horror myth than a real-life threat; a runaway ghost train.

Graph showing online interest in the Momo challenge as national media and the police pick up the story.

Source: The Guardian

Thankfully, most of these hoaxes are just that – circulating online, whipping up fear, and upsetting parents and children alike – although Carpenter warns of the dangers of "ostension." This is when "people will act out the stories and narratives they hear. There can always be one-off cases where a lone individual or two perform the premise of the hoax simply because it sparked the idea. Those cases are outliers, but they can happen. And that speaks to the importance of fact-checking sites."

"Prebunking" or "inoculating" people against misinformation and conspiracy theories is one way of counteracting zombie hoaxes. Social psychologist Sander van der Linden of the University of Cambridge, has created short, animated videos in collaboration with Google to educate users to spot and analyze common misinformation techniques.

The videos feature humorous techniques for spotting misinformation using characters from popular television shows and films like Family Guy and Star Wars. The results, published in Science Advances, said that those who watched the experimental videos were significantly better able to recognize manipulation techniques.

The non-profit organization the Brookings Institute, which aims to impact policy and governance through research, stresses that proper education and enhancing news literacy are possible solutions, stating that news organizations and tech platforms have a more significant role to play. One solution social media companies and news outlets could implement is a focus on accuracy, as studies have shown that people interact with information without focusing on whether the information is true.

MIT cognitive scientist David Rand and colleagues found that "when deciding what to share on social media, people are often distracted from considering the accuracy of the content." The study suggests that news and tech platforms could ask users to rate the accuracy of randomly selected headlines, a subtle way to remind them to examine the accuracy of the content.

As the Momo challenge illustrates, there's a fine line between warning against these hoaxes and spreading them. Carpenter agrees that there is no single or straightforward way to counteract this type of misinformation, though "data, truth, and awareness can help." He notes that local news organizations should be educated on reporting such events. Still, the crux of the issue lies with social media companies and whether they will enact more robust measures to limit the spread of harmful content through tighter platform restrictions.