By: Emilia Stankeviciute

October 9 2024

(Source: Internet Archive/U.S. Department of Justice/Dmitry Ant/Unsplash/buraktumler/Adobe/Modified by Logically Facts)

(Source: Internet Archive/U.S. Department of Justice/Dmitry Ant/Unsplash/buraktumler/Adobe/Modified by Logically Facts)

As we near the end of 2024, the shadow of Russian disinformation campaigns continues to loom over global elections.

In Europe, investigations by multiple national intelligence agencies revealed the extent of interference during the European Parliament elections. Russian-linked websites mimicked major news outlets such as Bild and Le Monde to disseminate false information aimed at undermining support for Ukraine and destabilizing the European Union.

U.S. federal authorities say similar tactics are now being deployed ahead of November's presidential election, where the Kremlin has been accused of using disinformation campaigns to influence voters.

These actions hark back to well-documented disinformation techniques used by the Soviet Union during the Cold War, but with modern twists that leverage digital platforms and AI. As nations worldwide grapple with these threats, understanding the historical roots of Russian disinformation strategies is crucial to countering their evolving influence today.

The Cold War, lasting from 1947 to 1991, was a global ideological struggle for influence between the United States and the Soviet Union, supported by their respective allies. While both the U.S. and the Soviet Union engaged in disinformation during the conflict, Soviet campaigns were systematic and deeply embedded within the state apparatus.

Dr. Inga Zakšauskienė, the Chief Archivist of Lithuania and a Doctor of Historical Sciences, explained to Logically Facts, "Soviet campaigns were always tied to broader geopolitical aims, from promoting Soviet ideology and culture to discrediting Western values."

For example, according to Soviet-era documents later made public, in the mid-1960s Russia's foreign intelligence service, the KGB, sought to stoke domestic racial tensions in the U.S. by insinuating government and white supremacist involvement in the civil rights movement. The KGB used a variety of techniques for this, such as planting articles critical of the U.S. government's response to the movement in an effort to unseat civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr, to spreading false propaganda inciting violence against the civil rights movement by a far-right Jewish group.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia revised and expanded its disinformation tactics, targeting Western democracies at critical moments.

According to a U.K. parliamentary report, during the 2016 Brexit referendum, accounts linked to the Russian troll factory the Internet Research Agency (IRA) pushed anti-European Union narratives. During the 2020 U.S. election, U.S. federal authorities found the troll factory targeted voters with tailored messages to polarize society and destabilize trust in electoral processes.

In 2024, the U.S. Department of Justice, in coordination with international partners, seized nearly 1,000 AI-driven fake social media accounts and two domain names linked to a Russian disinformation campaign. The same year, AI-driven disinformation was recognized as a major global threat, with the World Economic Forum's Global Risks Report warning that 91 percent of experts are concerned about its role in destabilizing societies and influencing elections and geopolitical conflicts.

Screenshots showing fake bot accounts and their posts on X. (Source: U.S. Justice Department)

Screenshots showing fake bot accounts and their posts on X. (Source: U.S. Justice Department)

Labeling political opponents as fascists or Nazis has been a central tactic of Soviet and, later, Russian disinformation for decades.

During the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, Soviet and Hungarian state media labeled the revolutionaries of the popular democratic movement as "fascists" and "imperialists." Soviet leaders framed their invasion of Hungary as necessary to protect the country from a fascist resurgence that happened during World War II. Similarly, during the Prague Spring in 1968, the Soviets labeled reformers as fascist counter-revolutionaries, allowing them to portray their invasion of what was then Czechoslovakia as a necessary intervention to preserve socialism.

This narrative was revived by Russia in 2014 during its annexation of Crimea. After the Ukrainian revolution ousted the pro-Russian president Viktor Yanukovych, Russian disinformation in state-controlled media and social media portrayed Ukraine's new government as being controlled by neo-Nazis, framing its annexation of Crimea as a necessary intervention to protect ethnic Russians and "de-Nazify" the region.

"Today, in Russia, state-controlled media plays a crucial role in executing disinformation operations while simultaneously supporting and concealing other state-led information programs," Zakšauskienė said.

In the ongoing conflict in eastern Ukraine, Russia has repeatedly deployed the Nazi label as part of its justification for military actions. In the lead-up to the 2022 invasion, Russian officials, including President Vladimir Putin, accused Ukraine of being controlled by neo-Nazis and committing genocide against Russian speakers.

Much like the Soviet accusations during the Cold War, these claims lack credible evidence. Ukraine's government, led by President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, who has Jewish ancestry, was widely recognized as legitimate by the international community. Zelenskyy has directly refuted these allegations, stating, "How can I be a Nazi? Explain it to my grandfather, who went through the entire war in the infantry of the Soviet army," referencing the fact that his family fought against Nazi forces during World War II, with several relatives being victims of the Holocaust.

While Russia has continually pushed the narrative of "denazification," there's no indication Russia is using the term to refer to far-right or fascist groups but rather as a broad label to demonize those it sees as opposing its ideological or geopolitical interests, framing Ukraine as an enemy of Russian values and statehood.

In fact, far-right groups in Ukraine, such as Svoboda, have minimal political influence. In the 2019 elections, Svoboda received only 2.15 percent of the vote and secured just one seat in the Ukrainian Parliament, making it largely irrelevant in shaping national policy.

The image shows a Soviet propaganda poster accusing "social fascists" of betraying the working class and collaborating with capitalist forces. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The image shows a Soviet propaganda poster accusing "social fascists" of betraying the working class and collaborating with capitalist forces. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

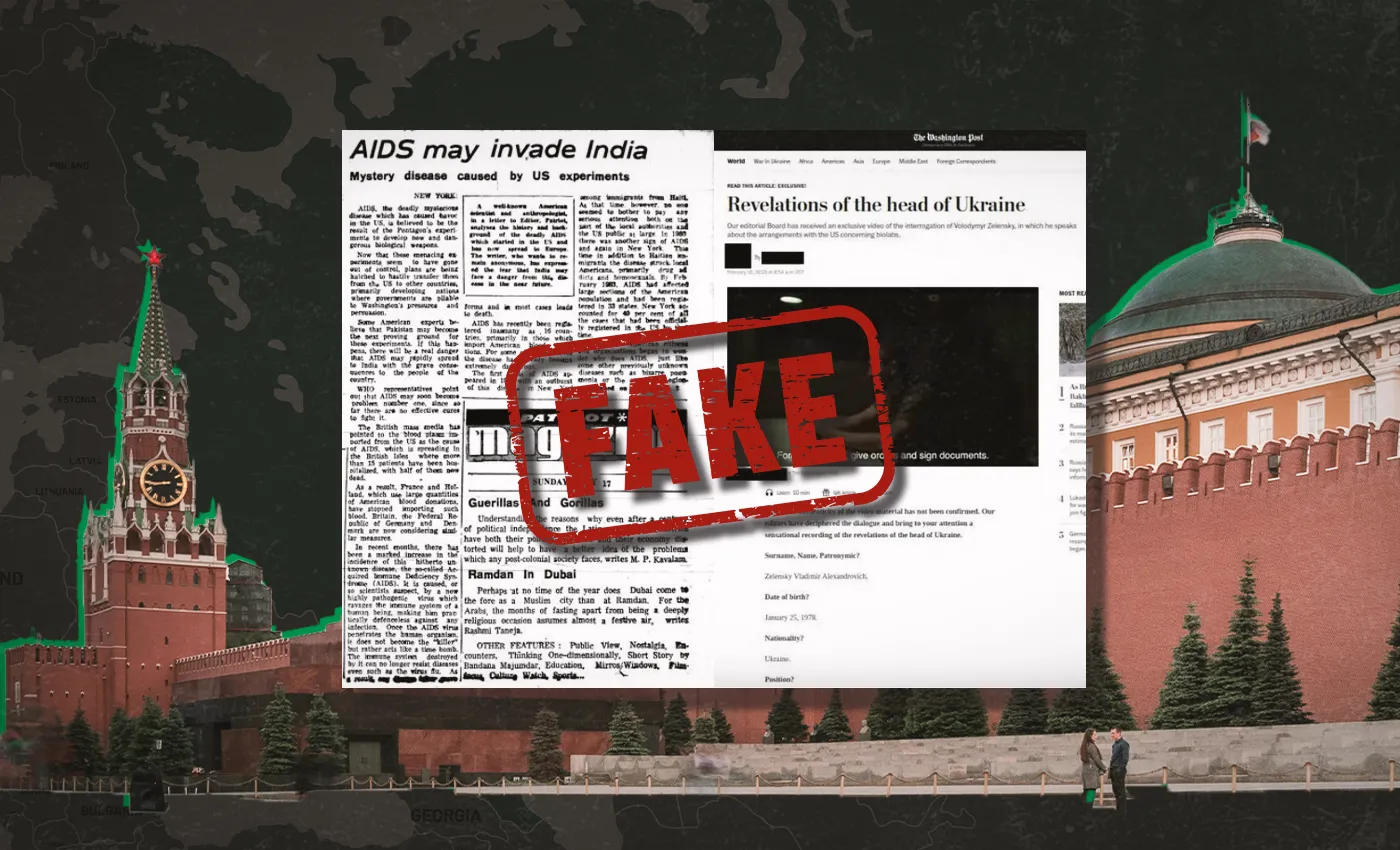

One of the most notorious Soviet disinformation campaigns during the Cold War was Operation Denver, which falsely claimed that the U.S. had developed HIV/AIDS as a biological weapon.

The disinformation campaign began with a planted letter in an Indian newspaper, "Patriot," in 1983, which baselessly blamed the U.S. for the global AIDS outbreak. According to declassified documents, Soviet and East German intelligence collaborated closely on this campaign, producing documentaries and promoting false claims through foreign journalists.

This narrative quickly gained traction, especially in developing nations, where historical mistrust of Western health initiatives was high, partly due to unethical experiments like the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, in which African American men were deliberately left untreated for syphilis over several decades. Soviet operatives exploited this distrust by spreading the story through media outlets in Africa, Asia, and beyond. Even mainstream Western media initially reported on the accusations, giving them unintended credibility before they were thoroughly debunked. For example, CBS News anchor Dan Rather reported on the story in 1987 without offering a rebuttal from the U.S. government.

Fast forward to the present, and Russia has revived similar tactics in its conflict with Ukraine, with Russian defense officials promoting the baseless claim that the U.S. is funding bioweapons labs in Ukraine. The narrative has been used to justify Russia's ongoing war, even though organizations, including the United Nations, have debunked the allegations. Russia spread similar disinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic, falsely claiming that the virus was a U.S. bioweapon.

"The persistence of biological weapons disinformation, as seen in the Cold War and now with COVID-19, is part of a broader strategy to exploit public fear," Dr. Olga Boichak, PhD, senior lecturer and director of the Computational Social Science Lab at the University of Sydney, told Logically Facts. "These claims not only undermine global health responses but also erode trust in institutions responsible for public safety, both domestically and internationally."

The Indian newspaper Patriot published a front-page article titled, "Aids may invade India: Mystery disease caused by U.S. experiments," in 1983. (Source: Internet Archive)

The Indian newspaper Patriot published a front-page article titled, "Aids may invade India: Mystery disease caused by U.S. experiments," in 1983. (Source: Internet Archive)

The 2016 U.S. election was by no means the first one in the country that Russia has attempted to influence. The KGB has been meddling in U.S. democratic processes as far back as 1984 when Soviet authorities painted President Ronald Reagan as a warmonger and heaped praise on his Democratic opponent in state media.

Russia's disinformation efforts continue in the lead-up to the 2024 U.S. election, mirroring historic Soviet strategies. Part of Russia's Doppelganger campaign, for example, involves creating fake websites mimicking legitimate media outlets to amplify pro-Trump narratives and undermine U.S. support for Ukraine. Russian state-run media has also covertly funded influencers to spread pro-Russian content across social media platforms, according to an indictment filed in early September by the U.S. Justice Department.

"Russia's digital influence operations have evolved in terms of targeting specific demographics, particularly in the West," Boichak told Logically Facts. "By using political micro-influencers, Russian disinformation is able to craft personalized, hyper-localized content aimed at niche groups. This tactic is particularly effective at influencing younger voters, who may not have the historical context to see through these tactics."

Outside of the U.S., the scale and scope of Russian cyberattacks within the EU have intensified in 2024. The attacks notably targeted countries like Poland and the Czech Republic and coincided with sensitive political periods, including the European Parliament elections in June. Russian hackers, such as the military-affiliated APT28 (also known as Fancy Bear), exploited vulnerabilities in widely used software, such as Microsoft Outlook, to gain unauthorized access to sensitive data. These attacks targeted governmental entities and compromised the email accounts of officials in these nations during the highly charged electoral period.

"Today, Russia's disinformation goals reflect the groundwork laid during the Cold War, but I would argue there is even greater opposition to the West, radicalizing Russian society and mobilizing it as a counterforce to the 'decadent West' and its values," Zakšauskienė said.

The fight against Russian disinformation remains both an official and societal struggle. During the Cold War, U.S. media outlets like Radio Free Europe (RFE) and Voice of America (VOA) played crucial roles in countering Soviet propaganda. Both bypass state-controlled media using satellite, digital platforms, and shortwave radio, allowing audiences to access Western content online even where broadcasting is blocked. In regions like Eastern Europe, RFE reaches millions weekly — in Lithuania, for example, it reaches 8.2 percent of the adult population.

As Russian disinformation has gone digital, so too have Western counterstrategies. In 2016, the U.S. launched the Global Engagement Center (GEC) to monitor and refute Russian claims, while the European Union's East StratCom Task Force, formed in 2015, fulfills a similar role in Europe, particularly following events like the annexation of Crimea.

Countries such as Ukraine and Estonia have taken proactive steps at the national level. Ukraine's Center for Countering Disinformation works closely with NATO and the EU, employing fact-checking and media literacy initiatives. At the same time, Estonia leads media literacy and digital defense efforts, utilizing volunteer networks like the "Baltic Elves" to counter disinformation.

Civil society has also stepped up. Groups like Bellingcat and the Atlantic Council's Digital Forensic Research Lab use open-source intelligence to uncover and dismantle false narratives, particularly in relation to Russia's activities in Ukraine.

While Russia now has new tools at its fingertips to disseminate disinformation more widely and rapidly, the narratives it relies on have their roots in the Soviet era.

"[Russian disinformation campaigns] will evolve by adopting ever newer technological capabilities — social media, artificial intelligence, bots, and deepfakes," Zakšauskienė told Logically Facts. "However, the core objectives will remain the same: to conduct subversive, decentralizing activities in countries with which Russia competes geopolitically for power and influence."