By: Ernie Piper

March 14 2021

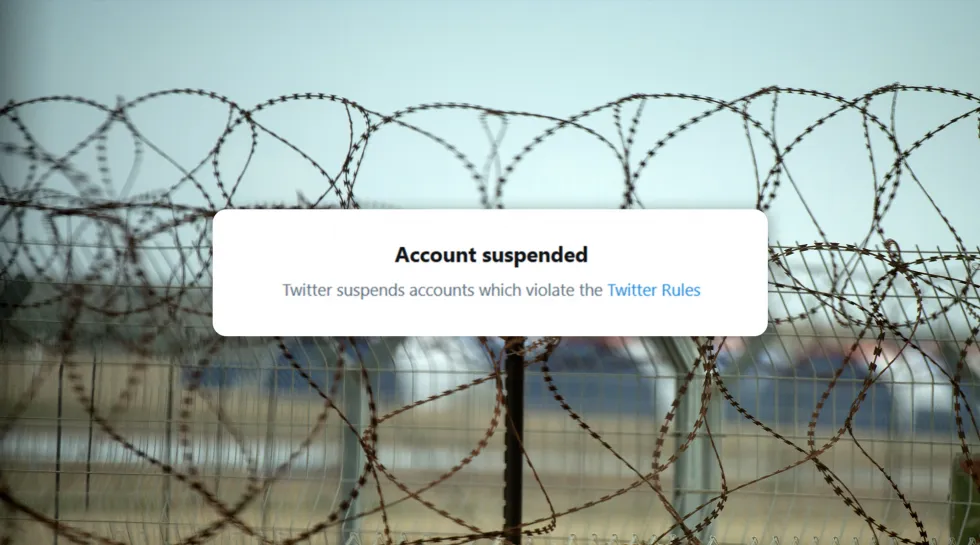

A Facebook group titled #SaveSheikhJarrah with 132k members taken down for review. A Palestinian writer who lost access to her Twitter account for posting footage of attacks on Gaza. A photograph of the al-Aqsa mosque, one of the holiest sites in Islam, removed from Instagram, for “promoting terrorism.” A TikTok account with more than 1.5 million followers fully blocked for sharing videos of Israeli forces attacking Palestinians.

These are merely the highest-profile cases in a wave of content removals and account suspensions across social media. Across the largest social media platforms, content from Palestinians depicting Israeli attacks is being taken down.

Although these posts are often matters of life and death, none of the largest platforms has any public policy regarding content moderation during an active conflict.

Content is removed under a patchwork of existing and unclear policies — violent content, harmful or dangerous content, content promoting terrorism. Often no reasons at all are given. Mona Shtaya, a local coordinator at Palestinian digital rights organzaiton 7amleh, highlighted in an interview with Al Jazeera that she had hundreds of cases of these kinds of content removals.

“Most of the content that was taken down was from Facebook and Instagram, and largely the account suspensions came on Twitter,” she said. “And then there are other cases of platforms hiding specific hashtags, like the #alaqsa hashtag.”

Instagram apologized and restored some of the content after activists brought it to their attention, blaming a technical glitch.

7amleh reported that it had received more than 200 complaints about content disappearing on Instagram alone related to the Sheikh Jarrah attacks. Instagram apologized and restored some of the content after activists brought it to their attention, blaming a technical glitch.

Often, social media channels are the only way for Palestinians to report on and document what is happening. It can be a matter of security, or of life and death.

Shtaya pointed out to Al Jazeera that Palestinians had received texts from Israeli security forces, telling them they had been identified to have been to the Al-Aqsa mosque, warning them not to return. Screenshots of these texts were circulating both as a call for awareness, and as a way to inform Palestinians of the danger of returning to the mosque.

“[Celebrities and influencers] are amplifying the human rights violations that are happening on the ground. This is extremely important for us.” Shtaya said.

“Thank God for social media.”

“Thank God for social media,” said Mohammed el-Kurd , a Palestinian writer who lives in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood, in an interview with Democracy Now, “because it appears that the world is finally waking up.”

Mohammed el-Kurd was also the one who tweeted on Thursday about Facebook taking down #SaveSheikhJarrah group.

Facebook and Twitter have policies towards violent content – and in Facebook’s case, they even acknowledge that some violent content can be used to raise awareness of issues. Both platforms carry separate policies for terrorism-related content.

Facebook’s policy on violence explains:

We remove content that glorifies violence or celebrates the suffering or humiliation of others because it may create an environment that discourages participation. We allow graphic content (with some limitations) to help people raise awareness about issues. We know that people value the ability to discuss important issues like human rights abuses or acts of terrorism.

However, as Facebook and Twitter partner with governmental organizations worldwide, including in Israel, it becomes much more difficult for stateless people to have equal representation.

However, as Facebook and Twitter partner with governmental organizations worldwide, including in Israel, it becomes much more difficult for stateless people to have equal representation. In a report from the Palestinian policy network Al-Shabaka, the authors write:

Another rule explains that “people must not praise, support, or represent a member…of a terrorist organization, or any organization that is primarily dedicated to intimidate a population, government, or use violence to resist occupation of an internationally recognized state.” As a result, Facebook has censored activists and journalists in disputed territories such as Palestine, Kashmir, Crimea, and Western Sahara.

The Israeli government has previously accused Facebook and Twitter of failing to prevent the spread of antisemitic or other content that promotes violence towards Israeli citizens, or the state of Israel at large. A Guardian report from 2016 explains that Facebook agreed to work with the government of Israel to remove content that targeted Zionists.

This goes beyond content removal, however. Al Shabaka reported that Israeli intelligence was partnering with Facebook in order to detect, monitor, and arrest Palestinians who they believed were likely to commit acts of terrorism.

The program monitors tens of thousands of young Palestinians’ Facebook accounts, looking for words such as shaheed (martyr), Zionist state, Al Quds (Jerusalem), or Al Aqsa. It also searches for accounts that post photos of Palestinians recently killed or jailed by Israel. The system thus identifies “suspects” based on a prediction of violence, rather than any actual attack – or even a plan to commit an attack.

Using this program, more than 800 Palestinians were arrested based on algorithmic identification. This report is from 2017, and there were no current numbers on whether this program continues to be used, or how many people have been targeted.

The stakes of digital rights in wartime are more than simply saving lives in the moment – they are also seen as a way to get justice in the future. Hadi al-Khatib, a video journalist who collected more than 1.5 million videos during the Syrian war, told the New York Times that he uses YouTube as an archive of human rights violations.

“The point is not just to bear witness, but to use these videos as evidence to prosecute perpetrators of war crimes,” he said.

All of the videos removed were claimed to have violated YouTube’s policy on violent or harmful content. Some 10 percent of his videos, or 200,000 clips, had been removed.

In an op-ed in Wired, the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, a think tank that promotes peace dialogues, argued that Facebook and Twitter could easily apply their policies towards monitoring speech around elections towards conditions of active conflict or war zones.

But even with clear-cut policies, tech platforms clearly bend to political pressure. An expose in the WSJ from August of last year found that Facebook's content moderators were instructed to leave up posts from leaders that contained phrases which violated their hate speech policies.

Three days ago, Netanyahu’s Arabic-speaking spokesperson Ofir Gendelmen tweeted a video of “Gaza right now,” with a video clip of rockets being shot towards Israel. The video, however, is two years old, and is publicly available on YouTube. Despite this misinformation, the post remained up for two days.