By: Ilma Hasan , Ishaana Aiyanna

September 8 2021

By Ilma Hasan and Ishaana Aiyanna

Last week, Madhya Pradesh’s Home Minister, Narottam Mishra, demanded action against Netflix for a kissing scene in the web series A Suitable Boy. The minister claimed that the kissing scene, which took place inside the premises of a temple, hurt religious sentiments.

Gaurav Tiwari, the BJP youth leader who filed the complaint that Mishra reviewed, also accused Netflix of promoting love jihad, a term used by Hindu nationalists to describe the unsubstantiated phenomenon in which Muslim men convince Hindu women to marry them, forcing them to convert to Islam.

This comes at a time the Indian government has been working towards regulating and censoring online content. In October, shortly before the Ministry of Broadcast and Information (MIB) announced that streaming platforms would now be regulated by the central government, Union Minister Prakash Javdekar told journalist Navika Kumar, “I receive hundreds of complaints every day on how [streaming platforms such as Netflix] are showing some objectionable programs. We need to figure these out soon.”

Javdekar may have been referring to a slew of claims that original Hindi content on streaming platforms is “hinduphobic”. “This is a very old technique,” Ankur Pathak, former entertainment editor of HuffPost India, told Logically. “You create an imaginary villain when there isn’t one, where you convince the populace that the majority is under threat.”

Indeed, Netflix series Sacred Games, Amazon Prime series Mirzapur, and more recently the MX Player series Aashram and Netflix’s Ludo have all been criticized for their Hindu imagery.

Prakash Jha’s Aashram has been labeled as “another web series which shows Hindu saints as criminals is nothing but an attack on the sentiments of Hindus who have been made subject to such hateful and demeaning portrayal in the media.” And Ludo was vilified for spreading “propaganda”. In November, director Vivek Agnihotri tweeted, “In this new film, 3 Indian Gods appear out of the blue and a little girl makes fun of them while they push the car. Why @Netflix why? Will you allow this with Gods of other faiths? I DARE YOU.”

Tweet by director Vivek Agnihotri on “Ludo”, released on Netflix this November.

In India, backlash over content, online or otherwise, is not new. A Logically investigation found that many users are intentionally spreading the false idea of “Hinduphobic propaganda” in digital content. The term Urduwood, which refers to the supposed domination of Bollywood by the “Khans” and other Muslim artists, has been used to spread this narrative.

Poll from @GemsOfBollywood

The term “Urduwood” has also become a trending hashtag. Logically found that a surge in engagement volumes of #Urduwood can be attributed to an account called @GemsOfBollywood in particular. Created in September, @GemsOfBollywood claims it wants to “work hard to bring out true perspective of Urduwood that is crucial for future of nation.” It now has over 72K followers, as well as a website that publishes reviews criticizing the depiction of Hinduism in popular culture.

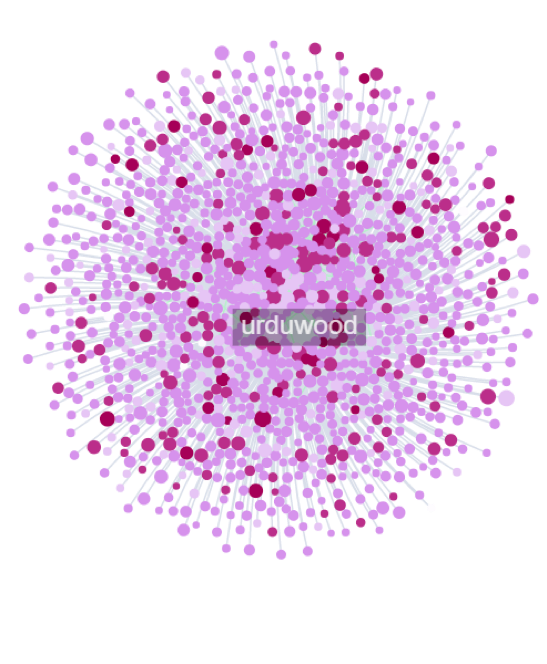

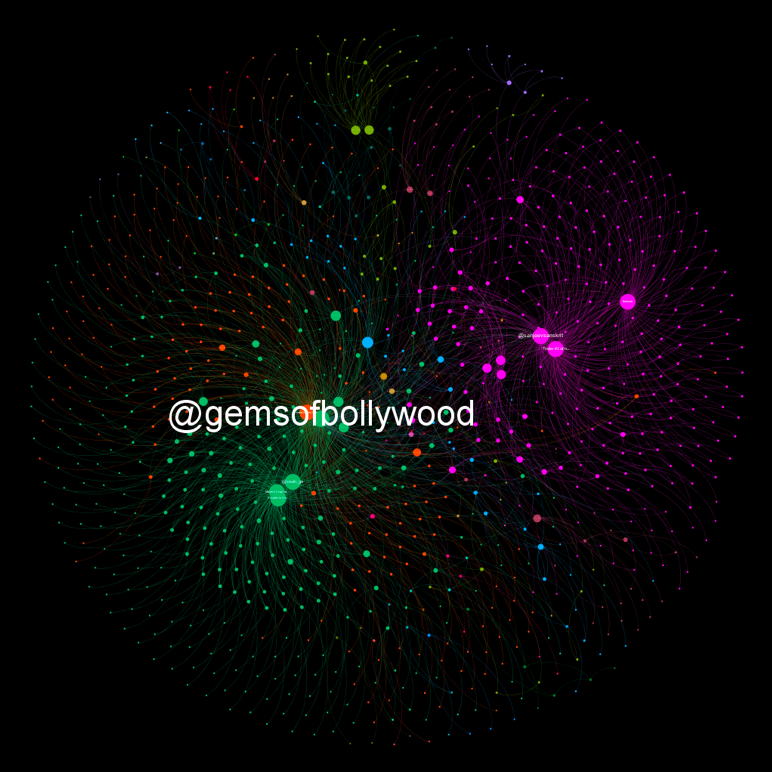

We also found that content from this page has been retweeted by a network of closely interlinked accounts. Most of these accounts have high automation scores, something that is indicative of bot and bot-like activity. Additionally, we found that these accounts are also the same handles that spread the hashtags #bringbacktrueindology, #censorlaxxmibomb, #censorerosnow, and #amitshahexpediteSSRcase.

This image depicts the influence of the #urduwood hashtag and the accounts that are spreading this information. The darker pink nodes indicate higher automation scores while lighter pink nodes indicate lower automation scores.

The Gems of Bollywood Twitter account is run by Swati Goel Sharma, a journalist who formerly worked for reputable media organizations but now works for the right-wing propaganda website Swarajyamag and Sanjeev Newar, the founder of multiple religion-based “welfare” groups. Newar is also followed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Although the website says that its writers “make no representation or warranty of any kind, regarding the accuracy of any information on the site or our mobile application,” they publish content that falsely claims Hindus are purposely denigrated in Hindi-language content. By posting clips ranging from old Hindi films to the latest Netflix series, and with over 240K followers between them, these writers are reinforcing the misleading narrative that Hindus have always been shown in bad light, and that this is due to the presence of Muslims in the Hindi film industry.

A disclaimer on the website

We have previously written about how trolls and bots control the reception of Bollywood films, but since the pandemic, trolls have been trying to control the reception of content on streaming services like Netflix.

@GemsOfBollywood organizes and amplifies what were once unorganized Twitter calls to boycott series and movies including Paatal Lok, Sadaak 2 and Raasbhari, by arguing that these movies represent “Hinduphobic propaganda”.

“We have had a very strong Urdu influence, with some of our oldest writers being Muslim. These were some of the most progressive and liberal writers,” according to Pathak. “But even if these disruptions existed in the past, one would be embarrassed to express these views because we all know they don’t hold any water, and they never did.”

Below is a Gephi visualization. Each color shows a group of interconnected and affiliated accounts that are retweeting the @GemsOfBollywood account, as well as the permutation of the conversation. We can see that Swati Goel Sharma and Sanjeev Newar are the most influential accounts, but other drivers of the conversation are @noconversion, @vikramsood and a host of closely related bot accounts. These users propel disinformation narratives by amplifying false content in large volumes.

Amplification of content from a newly formed @GemsOfBollywood

Does political leadership trigger these narratives?

Pathak believes this narrative is “100 percent being built from the government to the people” as a “systematic tool of suppression that has proven to be successful for the BJP”. According to him, the BJP government “has been very clever in exploiting the cultural power of cinema as an entry point to stir a conversation, and then use it as a weapon.”

“It is definitely orchestrated from the top, and is strategic because they decide what the narrative will be,” Shivam Singh, a former employee of the BJP IT cell who quit in 2018, told Logically. After his departure, Singh wrote in a blog post that his reason for resigning was the party’s affinity to spread misleading narratives, along with disseminating disinformation to create communal polarisation. “Even this idea of Urduwood in the entertainment industry fits well with the narrative they’re trying to push about the entire country in general,” he added.

In the past few years, the call for censoring or banning Netflix along with some of the content that streams on its platform has frequently trended on social media. Such trends have been in tandem with the central government’s attempts to push for regulation of digital content, and meetings held by Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh (RSS) with officials of online streaming platforms including Netflix and Amazon to restrict “anti-national” and “anti-Hindu” content on shows.

“Sangh Parivar is extremely uncomfortable. For instance, there have been many attempts to subvert the popularity of the Hindi film industry’s three leading men who happen to be Muslim. But they were unable to change the will of the people, which is why it’s interesting to see so many bot accounts,” Pathak said.

Singh agrees that these narratives don’t affect consumption, but rather help legitimize the government’s actions. “This will help them build consensus with their supporters, because till right now most people did not care. They built this narrative for the past few months, so they could justify [streaming services like Netflix] coming under the MIB.”

Javdekar has said that the government would prefer streaming services to self-regulate, and had given them 100 days to set up an adjudicatory body and finalize a code of conduct in March. But this month’s announcement has raised more questions about censorship.

From a disinformation perspective, what accounts like @GemsofBollywood do is spread unsubstantiated claims. These unsubstantiated claims are often borne out of reading too much into innocuous fiction, and often sow discord. They take the focus away from the content simply because it does not fit the bill of a Hindutva worldview. Such narratives help legitimize what the central government is trying to do.

“I think what we can expect is it starts with bot activity and little party support. But if they keep pushing this narrative it will become mainstream. This space was one they did not dominate and now they’re successfully moving towards it,” Singh says.

Started by the government, Pathak thinks such online activity has now gone beyond the government’s control. “Fault lines always existed, but it is not the job of the government to exploit them. They are successfully bringing out the worst in us. It’s like what they say about a riot, it can never be spontaneous.”