By: Francesca Scott

June 1 2022

The climate emergency is getting worse. Cyclical bouts of extreme storms, floods, droughts, and wildfires in the last year alone have affected millions of people worldwide. When the world locked down to curb the spread of COVID-19, NASA reported that although emission rates fell, CO2 in the atmosphere grew at the same pace as in the years when businesses were in operation. The pandemic had unpredictable effects on global plastic use and recycling, with people relying more on food delivery and hygienically wrapped items, not to mention the introduction of single-use face masks. Microplastics have been found in some of the most remote locations on earth, traveling there on the wind. They have also been found in the human placenta. CO2 and plastic, the byproducts of oil production, are destroying the natural world.

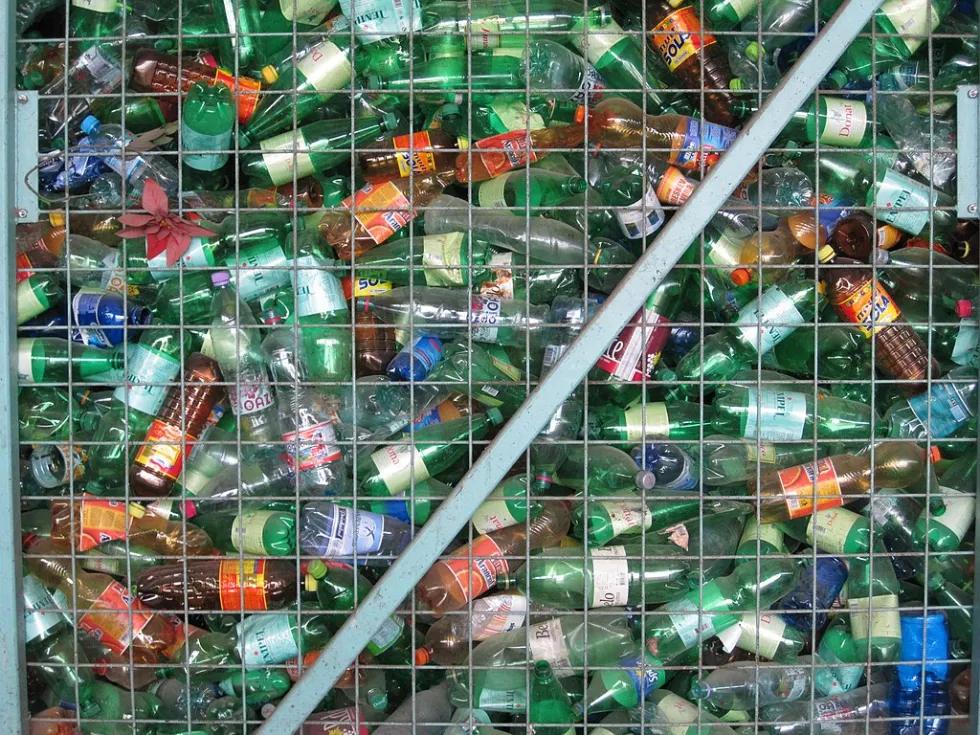

Recycling is sometimes touted as a solution to the environmental crisis, or at least the plastic crisis. That said, I've heard many people say that recycling is a scam; all our trash just gets thrown together, burned, or buried anyway, so there's little point in separating waste for recycling. A mixture of idealism towards solving a global problem, combined with a handful of dismal stories of waste being buried, burned and hidden, has made it difficult to find out whether plastic recycling does what it claims to do: reduce waste.

The statistics in some of the world's most prominent centers of industry don't provide much comfort. Research shows that in the U.S., only five to six percent of plastic waste was recycled in 2021, with 85 percent ending up in landfills and 10 percent incinerated. Similarly, a 2020 study by British Plastics Federation on U.K. plastic waste showed that just 10 percent was recycled, 17 percent went to landfill, and 46 percent was incinerated. Recycling in the U.K. fell from 44.5 percent in 2019 to 43.8 percent in 2020, sitting at number 25 in the Global Waste Index. Statistics across Europe vary, but Europa Stat reports that "each person living in the EU generated 34.4 kg of plastic packaging waste, out of which 14.1 kg was recycled" in 2019. In total, only an estimated 41 percent of plastic was recycled. The incineration of waste presents a range of consequences for the environment and people's health.

Recycling plastics is more complex than just melting everything together. There are seven categories of plastic, most of which aren't commonly recycled. White opaque and colored PET plastic is much harder to recycle than clear PET. The recycling process includes cleaning and decontaminating, separating and sorting, and finally shredding to flakes or melting into pellets. These pellets are then formed into new products.

Most of the world exported their waste, including recyclables, to China until 2017, when a ban was imposed that restricted 24 types of solid refuse. The impact of this was huge. Nature reported, “In 2018, the trade flow of global plastic waste plummeted by 45.5 percent, and China's imports plunged by 95.4 percent compared to Baseline levels.” Reuters discovered that, following the ban, waste exports were transported instead to countries in Southeast Asia, such as Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Thailand. Many Chinese plastic recycling operations set up processing plants illegally there to melt plastics, turn them into pellets, and then sell them back to China, which would use them in manufacturing. What was produced was caught by border officials, as oftentimes it was suspected of contamination or had low-grade plastic waste hidden among the pellets. Authorities shut down the illegal operations, and legislation was put in place in an attempt to stop such activities. Such a massive influx of waste moving from one area to another without proper systems in place to handle it wreaked havoc on the environment, and a black market plastic industry was born.

In a 2020 report by the BBC, it was found that "plastic that had been carefully sorted and separated by households in the U.K. was being sent to Turkey for recycling," where it was "being fly-tipped and burned." In response, Turkey imposed an import ban on July 2 of that year. Reuters has reported similar failures in the U.S. and elsewhere, particularly in the introduction of recycling initiatives aimed at repurposing hard to recycle plastics into low-polluting fuel. These projects – backed by companies like Unilever and Shell – fell apart, leaving stacks of separated plastics in the yards of empty recycling start-ups.

Some countries have implemented highly effective recycling systems. Germany leads the EU, with 67 percent of municipal waste recycled in 2021. Refillable glass bottles were introduced into circulation in the early 1990s along with a deposit reimbursed on return to supermarkets and bottle banks. People separate waste into color-coded trash cans, and fines are issued to individuals and businesses for improper recycling practices. Collection companies refuse to remove waste if it hasn’t been organized adequately.

Additionally, deterring manufacturers from overpackaging products has been an effective way to stem the problem at the source. HowToGermany reports that “The Green Dot system has been one of the most successful recycling initiatives, which has literally put packaging on a diet. The crux is that manufacturers and retailers have to pay for a "Green Dot" on products: the more packaging there is, the higher the fee.” South Korea follows similar approaches and sees around 60 percent of its waste recycled, with a risk of fines for incorrect disposal and a deposit return fee for single-use items. The Korea Times reports that the government is planning to reduce plastic waste by an additional 50 percent by 2050, including a ban on PVC and colored PET plastic.

Let’s be clear: both these countries still send tons of plastic waste to other countries. But what their successes tell us is that fee-deposit systems and fines work and should be implemented more widely.

The crux of the matter is that fossil fuel giants have obfuscated the realities of a constant stream of plastic production into the environment. Sure, we can recycle some plastic-like clear PET, but most cannot be recycled. Oil and gas companies not only know it, but have been knowingly hiding that information. A 2020 investigation by PBS' Frontline series discovered that "in the 1980s, the industry launched dozens of ads, nonprofits, and campaigns touting the benefits of recycling plastic – and placing the responsibility on consumers – even as their own documents warned that recycling was 'infeasible’ and that there was 'serious doubt' that plastic recycling 'can ever be made viable on an economic basis.'" In contrast to movements in Texas, California's attorney general Rob Bonta is opening an investigation into the oil industry's alleged deception of recycling. He said, "There is a broad belief that plastics are recyclable. That has been the result of the misinformation campaign, a deception. Consumers have been manipulated to believe that plastic is recyclable. It was a strategy as far as we can tell."

This is nothing new. There is a long history of oil companies reframing the narrative around pollution while lobbying against reforms that would cut emissions and limit extraction. Examples of the industry's attempts to gaslight the public range from the painfully clumsy 1970s "crying Indian" ad centering indigenous people as the victims of a polluting society, to Shell's spectacular climate poll fail that asked, "What are you willing to change to help reduce emissions?," to BP's branding of the carbon footprint. The industry's habit of laying the blame on individuals while continuing to expand gas and oil projects saw the recent public resignation of Caroline Dennett, a contractor at Shell. She stated, "Shell is operating beyond the design limits of our planetary systems. Shell is not implementing steps to mitigate the known risks. Shell is not putting environmental safety before production."

In a culture of rampant production, recycling systems are an integral part of sustainable infrastructure, but recent recycling statistics have shown that the process is not doing nearly enough. The bulk of the responsibility lies with the companies that produce the petroleum byproducts that make single-use plastics. As long as the oil and gas industry is alive and well, our planet will suffer the consequences, regardless of how much we recycle.