By: Nikolaj Kristensen

January 3 2024

Composite by Matthew Hunter

Composite by Matthew Hunter

Facing a crowd of reporters, staring down a camera lens, Lai Ching-te, Taiwan’s vice president and the ruling Democratic Progressive Party’s presidential nominee for the upcoming Taiwanese election, declares his primary opposition candidates from Kuomintang and Taiwan People's Party are Taiwan’s best bet for president and vice president. The clip has circulated in recent months on social media in Taiwan, where elections will be held on January 13.

The clip is a fake, generated by artificial intelligence to mimic the vice president’s voice. It exemplifies a growing challenge for the year ahead, where elections will be held in some 76 countries, covering more than half of the world’s population.

A screenshot of the deepfake widely circulated on social media in which Taiwan’s vice president Lai Ching-te expresses support for his main opposition in the upcoming election.

“Many, many countries will have elections in 2024, and there are fears and concerns that we will see more false claims that undermine confidence in voting processes and elections,” Angie D. Holan, director of the Poynter Institute’s International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN), told Logically Facts, a signatory of the IFCN. “This type of misinformation seems designed to undermine confidence in democratic processes, and it’s happening in many countries.”

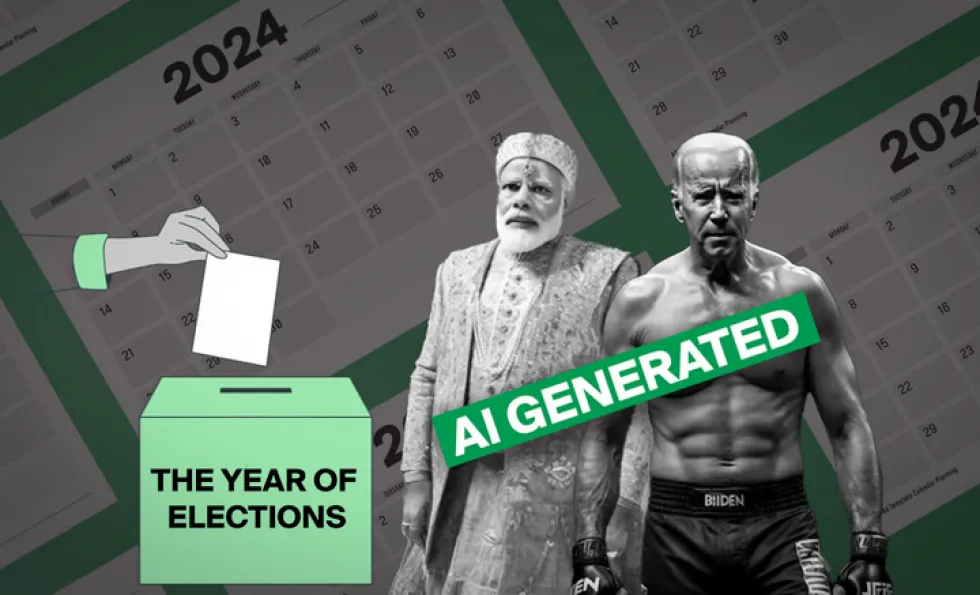

2024, dubbed “the biggest election year in history,” will see elections in some of the world’s most populous countries. India will hold general elections in April and May. The EU will hold European Parliament elections in June, and the U.S. will elect a president in November.

In the meantime, artificial intelligence tools have become widely accessible, allowing anybody to clone anyone else's voice and make realistic fake images and videos of anybody quickly and with little cost or effort. Generative artificial intelligence, which allows users to create new content based on prompts, became widely popular after the arrival of ChatGPT in November 2022.

The campaign of Florida governor Ron DeSantis used AI-tools to create images that showed Trump embracing and kissing Anthony Fauci. (Source: X/Screenshot)

Emerson T. Brooking, a resident senior fellow at Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab, told Logically Facts, “We're at a point now with advancements in generative artificial intelligence and with the sort of systematization of disinformation processes in many countries that I think it will be a great challenge to tell fact from fiction in the elections environment.”

As with the faked clip of Lai Ching-te, deepfakes and other content generated using artificial intelligence have already crept into election campaigns. Last year’s elections may have offered a taste of what’s to come.

Brooking said it still needs to be determined if the rise of AI-generated fakes will lead to more people being fooled or acting on falsehoods than before. But generative artificial intelligence will “inevitably” play a more significant role in the upcoming elections, he said: “We’ve seen it play a prominent part in the Slovakian election and the Argentinian election, and I suspect its frequency and visibility will increase.”

On September 30, 2023, Slovakia held general elections that saw the liberal Progressive Slovakia party lose in a tight race with SMER. A few days before the polls opened, an audio clip was shared on social media of what appeared to be Michal Šimečka, leader of Progressive Slovakia, in a discussion with a Slovakian journalist on how to buy votes. Šimečka denounced the clip as fake, and the French news agency AFP concluded the clip showed signs of AI manipulation. Slovakian election rules require politicians and media outlets to stay silent 48 hours before the polls open.

According to Brooking, the Argentine election saw AI-generated content and deepfakes becoming part of the election environment in a way we haven’t seen before: “There was less one specific deepfake, but a steady stream from both campaigns. In many ways, deepfakes were incorporated into more traditional campaign and political advertising exercises.”

Deepfakes and AI-generated content have also crept into traditional campaigning of the U.S. primaries. In April, when sitting president Joe Biden announced he would run for reelection in 2024, the Republican National Committee responded with an ad containing several AI-generated images depicting a dystopian future resulting from a Biden reelection.

Never Back Down, a super PAC supporting DeSantis, released a couple of ads manipulated using AI tools. In one, former President Donald Trump’s voice had been AI-generated to make it seem like he was narrating a tweet. DeSantis’ campaign also shared AI-generated images that showed Trump embracing and kissing Anthony Fauci.

Screenshots of the Republican National Committee AI-generated response ad to Biden's reelection bid. (Source: YouTube/RNC/Screenshots)

Other recent deepfakes from unknown sources have shown DeSantis dropping out of the Republican primaries and expressing support for Trump, former Democrat presidential candidate Hillary Clinton supporting DeSantis, and President Biden calling for a national draft to send troops to Ukraine.

Doreen Marchionni, editor of U.S.-based fact-checking site Snopes, told Logically Facts that she thinks the U.S. election misinformation this year will be even worse than previous. “Extremists on both the far left and the far right will continue to threaten our democracy and drown out everyone else in the middle,” she said. “Add to that mix the probable use of generative AI by bad actors, and we will be dealing with very scary, dangerous stuff.”

Jency Jacob, the editor of the Indian fact-checking website BOOM Live, predicts that India will face similar challenges in tackling AI-generated deepfake videos and cloned audio before the Spring elections. “The rapidly developing tools that make it easier for even those with low-tech skills to create deepfake videos are a cause of worry as the tools to detect the same are either not being built at the same pace or not being made available,” he told Logically Facts.

India’s Prime Minister Modi has recently raised concerns about the misuse of artificial intelligence and the proliferation of deepfakes on social media, calling it a “crisis.” India’s government has urged social media platforms to take action on deepfakes, stressing that platforms have a legal obligation, according to Indian legislation, to remove such content within 36 hours of receiving a report from a user or the government.

However, experts recently told Logically Facts that the regulation was too reactive to prevent deepfakes and similar content from causing harm.

Jacob says the best bet for countering deepfakes is to use manual methods of looking carefully at each suspect viral video and image. “But closer to elections, when the pace picks up, we will need more reliable tech to counter the dangers of large-scale disinformation," he added.

As if the proliferation and increased sophistication of generated fake images, videos, and audio at election time didn’t already spell enough trouble, the past years have seen social media platforms cut back on staff and policies put in place as a safeguard against mis- and disinformation.

After acquiring X, then called Twitter, Elon Musk fired many of the staff tasked with combating mis- and disinformation on the platform. X also reinstated several accounts previously banned for not complying with platform policy, most notably former U.S. president Donald Trump, who was suspended for inciting violence in the January 6 United States Capitol attack. Trump’s accounts have also been reinstated on YouTube, Instagram and Facebook.

Meta’s 2023 “year of efficiency” also saw several staff members committed to tackling disinformation and harassment on the platform laid off. In November, Meta announced that the company will now allow political ads that claim the 2020 election was stolen. Meta has said it will prohibit ads questioning the legitimacy of upcoming or ongoing elections.

YouTube announced in June that it would no longer remove content with false claims that the 2020 U.S. presidential election was stolen. The change did not apply to YouTube’s ad policy.

“There are all sorts of negatives that arise from cutting capabilities in this area,” Brooking said, adding that X had been “almost paralyzed” by misinformation since the layoffs and unable to deliver adequate responses.

“I think all tech companies will sort of feel that pain because they have reduced capacity at a time when governments around the world have an increased interest in these issues and are making serious demands on these companies,” he said.

The EU's Digital Services Act (DSA) will come into full force at the beginning of 2024. The act addresses systemic online risks such as disinformation. Thomas Regnier, EU Commission’s press officer for Digital Economy, Research and Innovation, told Logically Facts, calling the integrity of elections “one of the top priorities for DSA enforcement.”

The DSA requires platforms to assess risks stemming from the design or functioning of their service and employ measures to mitigate those risks, including those related to the protection of electoral processes. Regnier said that in light of upcoming elections, the platforms’ measures to prevent negative effects on democratic processes, civic discourse, and electoral processes will be carefully monitored. He added that AI-generated content – text, images, or videos such as those circulating online ahead of the Slovak elections – can contribute to risks under the DSA.

In December, the EU reached a provisional deal on its long-awaited AI Act. The act is expected to set a global standard for regulating the use of artificial intelligence.

On X, European Commissioner Thierry Breton broke news of the deal on EU’s AI Act, calling it “historic.” (Source: X)

The U.S. has been more hesitant to regulate AI. However, the Biden administration recently issued an executive order stating it “will help develop effective labeling and content provenance mechanisms so that Americans are able to determine when content is generated using AI and when it is not.”

Brooking said there seems to be a clear regulatory focus and interest in legislating the role of AI, especially in elections. Meanwhile, he notes, social media platforms have begun to understand this and so have their own incentives to invest in deepfake identification and labeling to reduce the prominence of deepfakes algorithmically. “It's a positive step that everyone is reaching this conclusion at once. But it’s likely not going to tackle the increased volume of disinformation entirely,” he said.

Robin Lee, a project manager from the Taiwanese fact-checking site MyGoPen, said disinformation regarding this year’s election took off after the presidential candidates were announced on November 24. “Already, we see something different from the last election,” Lee told Logically Facts. “Generative artificial intelligence has started to play a role. At this moment, we’ve seen disinformation videos about the election produced by generative artificial intelligence.”

Earlier in 2023, Taiwan’s outgoing president, Tsai Ing-wen, warned that the rise of AI has allowed disinformation to be generated and distributed at an unprecedented rate, with “authoritarian forces” attempting to influence and erode Taiwan’s democracy.

By the end of November 2023, Lee said, the MyGoPen team was still monitoring the disinformation and couldn’t yet estimate the scale. “But we expect to see more down the road as we get closer to the voting date,” he said.

Many more concerning developments lie ahead. One is the increasing systematization of disinformation that sees such campaigns kick into gear at the immediate onset of a major news event or crisis. Another is the so-called “liar’s dividend,” a tendency whereby the mere possibility of AI-generated fakes makes people distrust or discredit genuine images, videos, and audio, leading, in the worst case, to an overall loss of trust.

Then there’s the politicization of the mis- and disinformation field, where academics and researchers who study and uncover misinformation and disinformation campaigns have become targets of political attacks, hindering them from doing their jobs.

Brooking said that it’s not necessarily everything going wrong at once, but many developments present potential dangers. “Some of these developments may not turn out to be the big deals that we worry they might be.”